ODDS&ENDS: Weather Whiplash For Geniuses

Elon Musk is no dummy

THE SET-UP: Did you know that Elon Musk is a genius?

It’s true! Just ask Donald Trump or Bill Maher or Joe Rogan or anyone else who’s been awestruck (dumbstruck) by the fortune he’s amassed from the company he hijacked—Tesla— and the company he doesn’t actually run—SpaceX.

For them and millions more, Musk is a current-day version of the prolific inventor his car company is named after—Nikola Tesla. One quibble is that he didn’t “invent” Tesla, which was named by its two founders—Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. Musk was a funding guy who used his money and his connections to Silicon Valley’s venture capital community to go from fundraiser to board member to CEO and, now, to the face of the company. Despite the fact he didn’t invent anything, “Musk the Inventor” is treated as a well-established fact.

“Elon Musk’s 10 greatest inventions changing the world,” says the glowing headline from CNBC. Their subhead compares Musk with Thomas Edison. Wow, that’s even more impressive than Tesla! Edison invented the disc phonograph, electric generator, electric lamp, electric light and power system, electric pen, fuel cell, loud-speaking telephone, motion pictures. And that’s just a sampling of Edison’s handiwork. Then you read CNBC’s story and seven of Musk’s ten “greatest inventions” are … just companies. Not inventions … businesses. The other three are “an idea about allowing computers to call land lines” that never got off the ground, and idea for “location specific searches” on internet maps that didn’t turn into anything and a video game called Blastar he coded when he was twelve years-old.

And that makes him a modern-day Edison?

Of course not.

But Musk is a tech-savvy member of the PayPal Mafia who made a ton of money off a ground-floor bet on a wildly successful company. PayPal paid-off for Elon and Peter Thiel and Reid Hoffman and Max Levchin and a host of lesser-known names who went on to found a number of Silicon Valley companies and VC firms.

They are all definitely good at business and, specifically, the tech business. Does that make them “geniuses”? Is Elon Musk a “genius’?

Or is he an opportunistic businessman and surveillance capitalist who bought Twitter for the opinion-shaping megaphone and its wealth of data on hundreds of millions of humans? He’s certainly not a rocket scientist and he’s not managing SpaceX. That’s why he has the time to send out dozens of tweets on X and to hang out at Mar-a-Lago. He’s definitely not a climate scientist or an environmentalist. He didn’t actually found Tesla and he’s more than willing to pollute. His hatred of regulations is a response to government oversight of SpaceX’s terrible environmental record.

But we seem to reflexively believe Tesla somehow demonstrates his commitment to the climate. That’s just perception. The reality is this:

If Elon was a “genius” and he knew the “science” he’d know full-well that the risk is not “much slower.” In fact, it’s the exact opposite of “much slower.” Climate scientists around the world are now grappling with evidence that the change is accelerating. And it could be that they were not alarmist enough. But no … the “genius” has assured deniers and bigots everywhere that they are right … the devastation of the L.A. Fires is due to DEI and lesbian firefighters and the Delta Smelt and a panoply of culture war hot-buttons and dog whistles.

He’s no genius. But he is smart. And clever. And that leaves us with a question:

Does Elon actually believe the bullshit he’s shoveling?

Personally, I think he’s long-since tipped his hand. He knows we are in the midst of a global environmental crisis. That’s why he’s so desperate to get to Mars. - jp

TITLE: Floods, droughts, then fires: Hydroclimate whiplash is speeding up globally

https://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/floods-droughts-fires-hydroclimate-whiplash-speeding-up-globally

EXCERPTS: Los Angeles is burning, and accelerating hydroclimate whiplash is the key climate connection.

After years of severe drought, dozens of atmospheric rivers deluged California with record-breaking precipitation in the winter of 2022-23, burying mountain towns in snow, flooding valleys with rain and snow melt, and setting off hundreds of landslides.

Following a second extremely wet winter in southern parts of the state, resulting in abundant grass and brush, 2024 brought a record-hot summer and now a record-dry start to the 2025 rainy season, along with tinder-dry vegetation that has since burned in a series of damaging wildfires.

This is just the most recent example of the kind of “hydroclimate whiplash” – rapid swings between intensely wet and dangerously dry weather – that is increasing worldwide, according to a paper published today in Nature Reviews.

“The evidence shows that hydroclimate whiplash has already increased due to global warming, and further warming will bring about even larger increases,” said lead author Daniel Swain, a climate scientist with UCLA and UC Agriculture and Natural Resources. “This whiplash sequence in California has increased fire risk twofold: first, by greatly increasing the growth of flammable grass and brush in the months leading up to fire season, and then by drying it out to exceptionally high levels with the extreme dryness and warmth that followed.”

Global weather records show hydroclimate whiplash has swelled globally by 31% to 66% since the mid-20th century, the international team of climate researchers found – even more than climate models suggest should have happened. Climate change means the rate of increase is speeding up. The same potentially conservative climate models project that the whiplash will more than double if global temperatures rise 3 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The world is already poised to blast past the Paris Agreement’s targeted limit of 1.5 C. The researchers synthesized hundreds of previous scientific papers for the review, layering their own analysis on top.

Anthropogenic climate change is the culprit behind the accelerating whiplash, and a key driver is the “expanding atmospheric sponge” – the growing ability of the atmosphere to evaporate, absorb and release 7% more water for every degree Celsius the planet warms, researchers said.

“The problem is that the sponge grows exponentially, like compound interest in a bank,” Swain said. “The rate of expansion increases with each fraction of a degree of warming.”

The global consequences of hydroclimate whiplash include not only floods and droughts, but the heightened danger of whipsawing between the two, including the bloom-and-burn cycle of overwatered then overdried brush, and landslides on oversaturated hillsides where recent fires removed plants with roots to knit the soil and slurp up rainfall. Every fraction of a degree of warming speeds the growing destructive power of the transitions, Swain said.

Many previous studies of climate whiplash have only considered the precipitation side of the equation, and not the growing evaporative demand. The thirstier atmosphere pulls more water out of plants and soil, exacerbating drought conditions beyond simple lack of rainfall.

“The expanding atmospheric sponge effect may offer a unifying explanation for some of the most visible, visceral impacts of climate change that recently seem to have accelerated,” Swain said. “The planet is warming at an essentially linear pace, but in the last 5 or 10 years there has been much discussion around accelerating climate impacts. This increase in hydroclimate whiplash, via the exponentially expanding atmospheric sponge, offers a potentially compelling explanation.”

That acceleration, and the anticipated increase in boom-and-bust water cycles, has important implications for water management.

“We can’t look at just extreme rainfall or extreme droughts alone, because we have to safely manage these increasingly enormous influxes of water, while also preparing for progressively drier interludes,” Swain said. “That's why ‘co-management’ is an important paradigm. It leads you to more holistic conclusions about which interventions and solutions are most appropriate, compared to considering drought and flood risk in isolation.”

In many regions, traditional management designs include shunting flood waters to flow quickly into the ocean, or slower solutions like allowing rain to percolate into the water table. However, taken alone, each option leaves cities vulnerable to the other side of climate whiplash, the researchers noted.

“Hydroclimate in California is reliably unreliable,” said co-author John Abatzoglou, a UC Merced climate scientist. “However, swings like we saw a couple years ago, going from one of the driest three-year periods in a century to the once-in-a-lifetime spring 2023 snowpack, both tested our water-infrastructure systems and furthered conversations about floodwater management to ensure future water security in an increasingly variable hydroclimate.”

Hydroclimate whiplash is projected to increase most across northern Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, northern Eurasia, the tropical Pacific and the tropical Atlantic, but most other regions will also feel the shift.

“Increasing hydroclimate whiplash may turn out to be one of the more universal global changes on a warming Earth,” Swain said.

TITLE: SIERRA NEVADA CONSERVANCY: Weather whiplash in the Sierra-Cascade and the need to accelerate resilience

https://mavensnotebook.com/2025/01/08/sierra-nevada-conservancy-weather-whiplash-in-the-sierra-cascade-and-the-need-to-accelerate-resilience/

EXCERPTS: California’s mediterranean climate has natural cycles of wet and dry periods. However, large swings in precipitation are expected to become more severe as temperatures rise due to human-caused climate change. During the 2022 – 23 water year, 31 atmospheric rivers slammed into California resulting in record-breaking snowpack, whereas, just a year prior, the state experienced one of the driest January to March periods on record, deepening a three-year drought.

Bigger swings have bigger implications for the state’s water managers. As noted by Jay Lund, the Vice-Director for the Center for Watershed Sciences, “We are always going to have to worry about floods and droughts in California. If we manage it well, we won’t have to worry as much.”

The pendulum swing from heavy rainfall to hot summer temperatures could make matters worse. Elevated precipitation catalyzes plant growth which, when directly followed by hot temperatures, dries out, leading to heavy and flammable ground and understory fuels, increasing the risk of large high-severity wildfires.

Since 1900, only eight fires have burned more than 200,000 acres in the SNC service area. All of those fires occurred from 2012 – 2024.

Historically, fire swept through most parts of California’s Sierra-Cascade every 20 years or so and burned with a mixture of fire effects.

However, in many parts of the Region it has been more than 100 years since fire has burned through the landscape. This has led to many small trees growing close together and a lot of dead, dry wood on or near the ground. When fires burn through this kind of forest structure, they burn hotter and more severely, creating uncharacteristically large landscapes of dead trees.

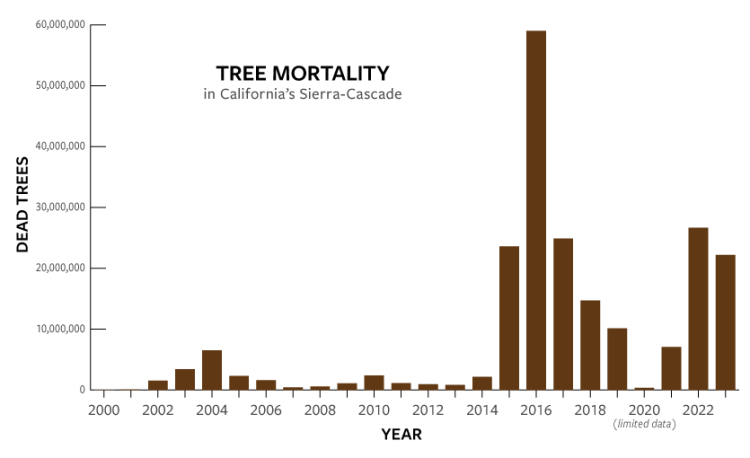

Large-scale tree mortality events are mainly driven by abnormally high temperatures and prolonged drought, as scarcity of water strains otherwise healthy trees. The lack of water supply is exacerbated by increased competition among trees located in unnaturally dense forests.

To date, tree mortality has disproportionately impacted large pines in the southern Sierra where more than a quarter of live trees are estimated to have died between 2012-2016. Signs of a new tree mortality event emerged in 2021 and 2022, this time among higher-elevation fir forests in the northern and central Sierra-Cascade.

Although forest-restoration projects are shown to be effective at mitigating risk from insects, drought, and wildfire, forest managers often feel outpaced by the additional stress and risk caused by extreme precipitation events, prolonged droughts, and increasing temperatures, all of which are driven by climate change.

The sheer pace of change occurring over the past decades underscores the need to accelerate our efforts to increase landscape and community resilience, as California simultaneously doubles down as a global leader in combatting climate change. It’s how the state can leave healthy, thriving, and forested regions to future generations.

TITLE: Earth breaches 1.5 °C climate limit for the first time: what does it mean?

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00010-9

EXCERPTS: It’s official: Earth’s average temperature climbed more than 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels for the first time in 2024.

“It’s both a physical reality and a symbolic shock,” says Gail Whiteman, a social scientist at the University of Exeter, UK, who studies climate risks. “We are reaching the end of what we thought was a safe zone for humanity.”

The announcement was made jointly by several international organizations that independently track the global temperature. Although each group calculated a slightly different figure, averaged together the data indicate a consensus that, last year, Earth’s temperature hit 1.55 °C above the average for 1850–1900 — considered to be a ‘pre-industrial’ period before humans began pouring large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Unexpectedly, the 2024 figure also shows a statistically significant increase over that for 2023, when heat records were set. Climate scientists are investigating whether the two-year temperature surge is a blip or whether it marks a change in Earth’s climate system that means global warming is speeding up.

To filter out noise — normal climate variations — from the temperature data, scientists often report a ten-year average. This allows them to zero in on Earth’s long-term temperature trend, improve models and build better projections going forwards. By this measure, researchers estimate that the world has warmed to 1.3 °C above pre-industrial levels, and it could be several more years before 1.5 °C is well and truly breached. That extra time matters.

“We are still living in a 1.3 °C world” in terms of air temperature, says Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy, a conservation group based in Arlington, Virginia. Most of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases is absorbed by Earth’s oceans, land and ice, she adds. By the time the ten-year average for the air tops 1.5 °C, the planet will have accumulated even more heat, further amplifying violent storms and fires, ecosystem damage and sea-level rise.

Scientists stress that there is nothing magical about the 1.5 °C threshold. It is a political target that was included in the Paris agreement in acknowledgement of concerns that an earlier goal of limiting warming to 2 °C might not be strong enough to protect the most vulnerable countries, including island nations at risk of being submerged by rising seas. That does not mean the world is safe below 1.5 °C, nor that everything will suddenly fall apart if it is breached. It’s a spectrum, Hayhoe says, “and every bit of warming matters”.

One worry is that the news that the 1.5 °C limit has been breached will spur complacency rather than action, Whiteman says. People who tend to be more sceptical about the dangers of global warming might think, “See? We crossed that line and nothing happened.”

But the impacts of extreme weather events and the long-term risks of melting ice and shifting ecosystems will continue to mount, unless and until humanity stops pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

“The impacts are already hitting the ground now,” Whiteman says. “And they will get worse.”