DAILY TRIFECTA: Plastic Man Of The People

Trump sucks (through a straw)

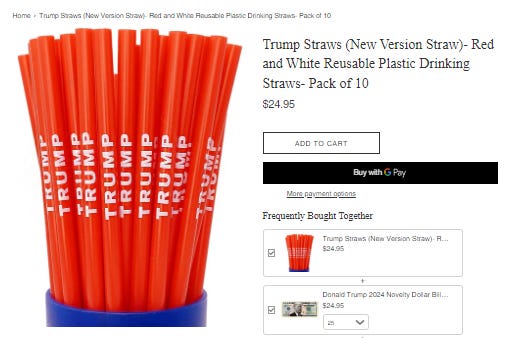

REMINDER: In a bid to “own the environment” back in 2020, the Trump campaign launched a line of plastic straws:

That’s right, back then you could suck unrepentantly and then show Mother Earth who’s boss by throwing it out of the window of your coal-rolling truck.

But Trump devotees who still want to suck are now greeted by different pitch on the official website:

Yup, the “New Version Straw” is still plastic, but its marketed as “Reusable.” Whether or not people actually wash and reuse these straws, it is a marked difference in tone.

Of course, it’s just marketing, much like the petrochemical industry’s successful, phony-baloney “recycling” campaign. The illusion of recycling has given the industry, and consumers, a pass. And a “pass” is exactly what the petrochemical industry expects to get out of Trump’s second term. In fact, it’s already started. - jp

TITLE: What a Trump Win Means for the Plastics Industry

https://www.plasticstoday.com/industry-trends/what-a-trump-win-means-for-the-plastics-industry

EXCERPTS: “If you’re in the plastic production business, you might just be praying for a Trump victory on Nov. 5,” wrote Politico the day before Election Day. Those prayers, needless to say, were answered.

The gist of the Politico story was that a Trump administration would almost certainly be a spoiler in the forthcoming United Nations–led binding global treaty to end plastic pollution. The fifth — and final — negotiating session is coming up at the end of this month in Busan, South Korea. Ahead of that meeting, the Biden administration revealed a startling policy shift: In August, it announced that it would support a reduction in the production of new plastics, aligning it with the more progressive wing — Canada and the European Union, among others — taking part in the negotiations. To no one’s surprise, the plastics industry by and large opposes this approach to reducing plastic pollution.

Regardless of who sits in the Oval Office, the United States has a poor track record of ratifying international treaties. Under Trump, that reluctance will be turbo-charged. He is no fan, to put it mildly, of multinational agreements, and the idea of scaling back production of anything, let alone fossil-fuel-based products, is bound to be a non-starter.

“A Trump election would really spell doom, I think, for a strong treaty, at least one that includes the United States,” Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.), who joined a congressional delegation at the last round of negotiations in Ottawa, told Politico. “Under a Trump administration, there's no doubt that the US would fall in with Russia and the Saudis and the other petrostates and the fossil fuel industry and support a treaty that probably makes for a good media cycle, but is really just a permission structure for plastic pollution and for the fossil fuel industry to continue business as usual.”

A Trump win would also be a major score for oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Russia, who have been accused of purposely torpedoing the UN talks, added Politico.

The talks will resume for a final round in Busan on Nov. 25, leading to the final text of a global plastics treaty before the end of the year. Some observers expect the talks to go into overtime, allowing the Trump administration to “exert more influence,” writes Politico. Would it matter, though?

It’s clear to me, at least, that the treaty, and especially the notion that the best way to reduce plastic pollution is to scale back plastic production, will go nowhere in the United States. And for the vast majority of the plastics industry, that is, indeed, an answered prayer.

TITLE: The US no longer supports capping plastic production in UN treaty

https://grist.org/regulation/us-backtracks-production-caps-global-plastics-treaty-united-nations/

EXCERPTS: The Biden administration has backtracked from supporting a cap on plastic production as part of the United Nations’ global plastics treaty.

According to representatives from five environmental organizations, White House staffers told representatives of advocacy groups in a closed-door meeting last week that they did not see mandatory production caps as a viable “landing zone” for INC-5, the name for the fifth and final round of plastics treaty negotiations set to take place later this month in Busan, South Korea. Instead, the staffers reportedly said United States delegates would support a “flexible” approach in which countries set their own voluntary targets for reducing plastic production.

This represents a reversal of what the same groups were told at a similar briefing held in August, when Biden administration representatives raised hopes that the U.S. would join countries like Norway, Peru, and the United Kingdom in supporting limits on plastic production.

Jo Banner, co-founder and co-director of The Descendants Project, a nonprofit advocating for fenceline communities in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” said the announcement was a “jolt.”

“I thought we were on the same page in terms of capping plastic and reducing production,” she said. “But it was clear that we just weren’t.”

Frankie Orona, executive director of the nonprofit Society of Native Nations, which advocates for environmental justice and the preservation of Indigenous cultures, described the news as “absolutely devastating.” He added, “Two hours in that meeting felt like it was taking two days of my life.”

The situation speaks to a central conflict that has emerged from talks over the treaty, which the U.N. agreed to negotiate two years ago to “end plastic pollution.” Delegates haven’t agreed on whether the pact should focus on managing plastic waste — through things like ocean cleanups and higher recycling rates — or on tamping down the growing rate of plastic production.

Nearly 70 countries, along with scientists and environmental groups, support the latter. They say it’s futile to mop up plastic litter while more and more of it keeps getting made. But a vocal contingent of oil-exporting countries has pushed for a lower-ambition treaty, using a consensus-based voting norm to slow-walk the negotiations. Besides leaving out production limits, those countries also want the treaty to allow for voluntary national targets, rather than binding global rules.

Exactly which policies the U.S. will now support isn’t entirely clear. While the White House spokesperson told Grist that it wants to ensure the treaty “addresses … the supply of primary plastic polymers,” this could mean a whole host of things, including a tax on plastic production or bans on individual plastic products. These kinds of so-called market instruments could drive down demand for more plastic, but with far less certainty than a quantitative production limit. Bjorn Beeler, executive director of the nonprofit International Pollutants Elimination Network, noted that the U.S. could technically “address” the supply of plastics by reducing the industry’s projected growth rates — which would still allow the amount of manufactured plastic to continue increasing every year.

“What the U.S. has said is extremely vague,” he said. “They have not been a leading actor to move the treaty into something meaningful.”

Another apparent change in the U.S.’s strategy is on chemicals used in plastics. Back in August, the White House confirmed via Reuters’ reporting that it supported creating lists of plastic-related chemicals to be banned or restricted. Now, negotiators will back lists that include plastic products containing those chemicals. Environmental groups see this approach as less effective, since there are so many kinds of plastic products and because product manufacturers do not always have complete information about the chemicals used by their suppliers.

Viola Waghiyi, environmental health and justice program director for the nonprofit Alaska Community Action on Toxics, is a tribal citizen of the Native Village of Savoonga, on the island of Sivuqaq off the state’s western coast. She connected a weak plastics treaty to the direct impacts her island community is facing, including climate change (to which plastics production contributes), microplastic pollution in the Arctic Ocean that affects its marine life, and atmospheric dynamics that dump hazardous plastic chemicals in the far northern hemisphere.

The U.S. “should be making sure that measures are in place to protect the voices of the most vulnerable,” she said, including Indigenous peoples, workers, waste pickers, and future generations. As a Native grandmother, she specifically raised concerns about endocrine-disrupting plastic chemicals that could affect children’s neurological development. “How can we pass on our language, our creation stories, our songs and dances, our traditions and cultures, if our children can’t learn?”

TITLE: The plastics crisis is now a global human health crisis, experts say

https://news.mongabay.com/2024/11/the-plastics-crisis-is-now-a-global-human-health-crisis-experts-say/

EXCERPT: [T]alking about plastic as a litter problem ignores one of the most alarming facets of our plastic addiction: its impacts on human health.

Fast-mounting evidence points to microplastics entering the human body and doing internal damage. Likewise, thousands of chemicals that leach out of plastics are finding their way into our bodies (via food wrappers, storage containers, cooking utensils and other routes) with some of those chemicals linked to a range of health impacts, including immune suppression and cancer.

In a new report out Nov. 7th in the journal One Earth, an international group of researchers attempted to gather all of plastic’s myriad negative impacts into a global framework ahead of the final round of negotiations for a global plastics treaty scheduled to run Nov. 25 to Dec. 1 in Busan, Korea.

The report puts it bluntly: “Despite the manifest benefits of plastics, plastics pollution now threatens the environment, food security, and human health.”

The trouble starts at the very beginning of the supply chain, when petroleum is extracted and processed into the petrochemical ingredients for plastic.

Plastics are often marketed as if they are simple, pure polymers — labeled, for example, as polyester, polyurethane, PVC and more. And while we do know that PVC and polystyrene can leach hazardous substances such as styrene, phthalates and vinyl chloride, there are other dangers lurking in these generically labeled polymers.

Plastic packaging, toys, clothing, kitchenware and construction materials almost always include a proprietary mix of chemicals: processing aids and additives such as plasticizers, flame retardants and pigments, which can make up to 70% of their weight, according to the One Earth report.

Some of these chemicals are known to be carcinogenic, mutagenic and reproductively and developmentally toxic. Of the more than 16,000 chemicals used to make plastic, or present in plastic materials and products, more than 4,200 — up to two–thirds of the chemicals used or found in well-studied plastic types — are of concern because they are persistent, bioaccumulative, mobile and/or toxic. Hazard information is lacking for another 10,000.

But research has shown that these chemicals don’t stay inside plastics; untold numbers of them, in unknown amounts, end up inside us. A study published in September found that more than 3,600 chemicals are found in both plastic food packaging and in human blood, indicating that these chemicals are leaching out of plastics — whether from packaging into food or from microplastics that we ingest into our bodies.

Researchers are scrambling to understand what plastic and its chemical additives are doing to us, an effort greatly slowed by a stunning lack of transparency from the petrochemical industry as to what chemicals are in what plastics.

But scientists are increasingly warning that the rising rates of cancer, lung disease, infertility and obesity are due not solely to lifestyle factors but to environmental pollutants, including those in plastics. For example, a May 2024 study linked higher rates of breast cancer to the presence in outdoor air of chemicals used to make polystyrene and PVC plastics.

Of particular concern are plasticizers, or endocrine disrupting chemicals added to plastics to make them soft and pliable, including BPA and its many bisphenol cousins and phthalates. PFAS, a toxic class of chemicals known as “forever chemicals” because they never break down or go away, are also endocrine disruptors and often found in plastics.

Hormone disrupting chemicals have been associated with hormone-related cancers, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. A 2020 meta analysis showed that people with higher levels of endocrine disruptors in their bodies were more likely to be obese. A 2022 study showed that the presence of more endocrine disruptors in the bodies of women trying to get pregnant was associated with a lower chance of success.

Plastic makers have traditionally proposed recycling as the solution to the plastics crisis. But recycling done wrong can amplify plastic’s toxicity. Take for example, black plastic spatulas, takeout containers and even children’s toys were recently found to contain high levels of flame retardants and flagged as a public health problem. That’s because the black plastic used to make electronics (which can be toxic and was never intended for use in connection with food) is frequently recycled in developing nations (where there is little to no regulation or oversight) and turned into new plastic products.

Plastic products continue to be a potential source of toxins even after disposal. While a single-digit percentage of plastics get recycled, an estimated 14% of all the plastic ever created has been incinerated, which can release plastics into the air and environment in the form of tiny particulates (linked to lung and heart disease), heavy metals such as lead and mercury and dioxins, which have been linked to impairment of the immune system, reproductive system and the development of the nervous system in children.

The other huge public health problem with plastics arises when they start to degrade — either in our homes while we’re using them, or after they end up in the environment. Plastics over time degrade into smaller and smaller pieces. The result is microplastics, which are found everywhere on Earth.

Microplastics from many sources find their way into our bodies in a typical day: Plastic microfibers are shed from clothing and furnishings; nanoplastics leach out of food packaging and containers (especially when we microwave them). Microplastics are found in the produce we eat, tap water and, especially, bottled water, beer, seafood and the air we breathe. One study found that microplastics can end up in baby formula when it’s prepared in polyethylene bottles.

They’ve also been found throughout the human body — in brain tissue, lungs, placentas, breast milk, livers, testes and blood. The microscopic plastics found in humans range from PET (used in polyester clothing and plastic water bottles) to polyethylene (stretchy plastic, milk jugs and shampoo bottles) and PVC (shower curtains, vinyl construction products and clear plastic fashion accessories).

How microplastics interact with human organs or how they impact body function remains largely unknown, as microplastics and health is a new field of study. But alarm bells are already sounding in the scientific community.

A study published in March found that half of patients with asymptomatic cardiovascular disease had microplastics in their carotid artery plaque and were at higher risk of a heart attack, stroke and death in the next three years than those who did not. A similar correlation has been found between the presence of microplastics in feces and inflammatory bowel disease. In the lab, microplastics can be deadly to human cells.

Rodent studies have shown that microplastics affect the lungs, liver, intestines and the reproductive and nervous systems. And at least one of those rodent studies found that even “clean” microplastics that are free of hazardous additives can cause health problems.

When confronted with these alarming public health studies, some people look for ways to reduce their personal exposure to plastic, microplastics and additives.

But because plastics and microplastics are ubiquitous — because there are no mandated disclosures about what is in plastic products and because so many chemicals in plastics have never been analyzed for their health impacts — it has become an impossible task for individuals or communities to avoid plastic’s harms altogether.

“Plastics are seen as those inert products that protect our favorite products or that make our lives easier that can be ‘easily cleaned up’ once they become waste. But this is far from reality,” says PhD candidate Patricia Villarrubia-Gómez at the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University and lead author of the One Earth report. “Plastics are made out of the combination of thousands of chemicals … with which we interact on a daily basis.”