DAILY TRIFECTA: Making Glyphosate Great Again

Verbicidal Maniacs

THE SET-UP:

Homicide. Suicide. Fratricide. Genocide.

Pesticide. Fungicide. Herbicide.

That sharp-sounding suffix portends the same fate for brothers, beetles and begonias alike. It’s death in one syllable. Or, as etymonline.com more accurately explains, “cide” is:

…a word-forming element meaning "killer," from French -cide, from Latin -cida "cutter, killer, slayer," from -cidere, combining form of caedere "to fall, fall down, fall away, decay, fall dead."

That killer suffix reverberates in my mind’s ear whenever I see a suburban gunslinger pulling the trigger on a yellow and green spray-bottle loaded with Roundup. A quick strafing run is enough to kill nettlesome interlopers in the grass or to decimate invaders along the cracks and seams of a driveway.

It’s been a game-changer in the war on weeds.

That’s because the herbicide also known as glyphosate has an uncanny ability to kill weeds while sparing lawns and crops—particularly crops genetically engineered to be “Roundup Ready.” Almost like a neutron bomb … which kills the people you don’t want, but leaves the buildings you covet intact. In a sense, you can spray ‘em all and let glyphosate sort ‘em out. That nifty “innovation” helped make it humankind’s most widely-used chemical killer.

Although, “chemical killer” sure doesn’t sound like something you’d want to spray on your lawn, particularly if your kids run barefoot or roll around on it. It might also give you pause if you have pets. [insert pun here] Or maybe you are regular golfer? Or simply enjoy reclining on the grass in a municipal park?

“Chemical killer” also doesn’t sound like something you’d want on your vegetables or infused into your Cheerios.

Even “herbicide” is kinda ominous, particularly after a number of civil trials found that “herbs” might not be the only thing glyphosate “cides.” That, in turn, has compelled Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, to settle nearly 100,000 Roundup-related lawsuits to the tune of almost $11 billion. And there’s plenty more where that came from.

What glyphosate really needs now is a re-brand.

So, instead of herbicide or chemical killer, how about … “crop protection tool”?

Yeah, that’s much better. It’s a bit like changing the War Department to the Department of Defense, only more so. Every word has a positive connotation. Crops. Crops are good. They grow and they feed people. Protection is warm and safe and vigilant. It doesn’t kill unless there is no other option. And what’s better than a tool? Tools fix problems. Tools build things.

So, forget all this talk of “cide” and death … glyphosate isn’t that … it’s a tool we use to protect crops … it’s safe and warm. Almost heroic, really. And, like many carefully crafted, strategically deployed euphemisms … it’s also bullshit. Or, more pointedly, it’s an act of verbicide.

Yes, according to dictionary. com, that’s a real word that refers to “the willful distortion of the original meaning of a word.” It’s been around since “the first half of the 19th century,” but it’s made for the 21st Century. After twice electing a verbicidal maniac, I am not sure if there’s a word more emblematic of the socio-political quagmire we find ourselves in. Nor is there a word better suited to RFK Jr.’s handling of glyphosate in his just-released “Make America Healthy Again” report.

The one-time environmental crusader and long-time critic of glyphosate spent the lead-up to today’s big reveal reassuring agitated Republicans and anxious farmers that he would not cast glyphosate in the starring role of America’s most poisonous villain. Still, they fretted … and for good reason. As recently as September of last year he told Dr. Phil that farmers were “mass poisoning” America’s kids, and the first poison he mentioned was glyphosate.

Now the report is out. And you’ll find the relevant portions excerpted below, along with excerpts from two other relevant stories. I searched for “glyphosate” and it only appeared in the body of the report twice. It did appear a four times in the footnotes. “Herbicides” appeared twice in the same place and twice in the footnotes. A similar search for “pesticides” produced nine mentions in the text and three in footnotes. While “pesticides” popped-up a few times in lists of chemical contaminants, “herbicides” and “glyphosate” did not.

Most notably, the herbicide called glyphosate was not categorized as the cause of “mass poisoning.” Far from it. Instead, the report categorized it as a “crop protection tool” and vaguely referred to “the most common herbicide” (a.k.a. “glyphosate”?) being safe when used “according to label directions.”

If nothing else, the report may inspire us to tack “cide” onto the end of the word “irony.” - jp

TITLE: The ‘Make America Healthy Again’ Report

https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/WH-The-MAHA-Report-Assessment.pdf

FYI: I used this link to download the PDF:

https://static01.nyt.com/newsgraphics/documenttools/fd441e56ad4bcf36/2f18e38b-full.pdf

EXCERPTS:

Crop Protection Tools: including pesticides, herbicides, and insecticides. Some studies have raised concerns about possible links between some of these products and adverse health outcomes, especially in children, but human studies are limited. For example, a selection of research studies on a herbicide (glyphosate) have noted a range of possible health effects, ranging from reproductive and developmental disorders as well as cancers, liver inflammation and metabolic disturbances. In experimental animal and wildlife studies, exposure to another herbicide (atrazine) can cause endocrine disruption and birth defects. Common exposures include lawn care, farming, and pesticide residues; however, a large-scale FDA study of pesticide residues (2009-2017) found the majority of samples (>90%) were compliant with federal standards. More recent data from the USDA's Pesticide Data Program found that 99% of food samples tested in 2023 were compliant with EPA's safety limit. Federal government reviews of epidemiologic data for the most common herbicide did not establish a direct link between use according to label directions and adverse health outcomes, and an updated U.S. government health assessment on common herbicides is expected in 2026.

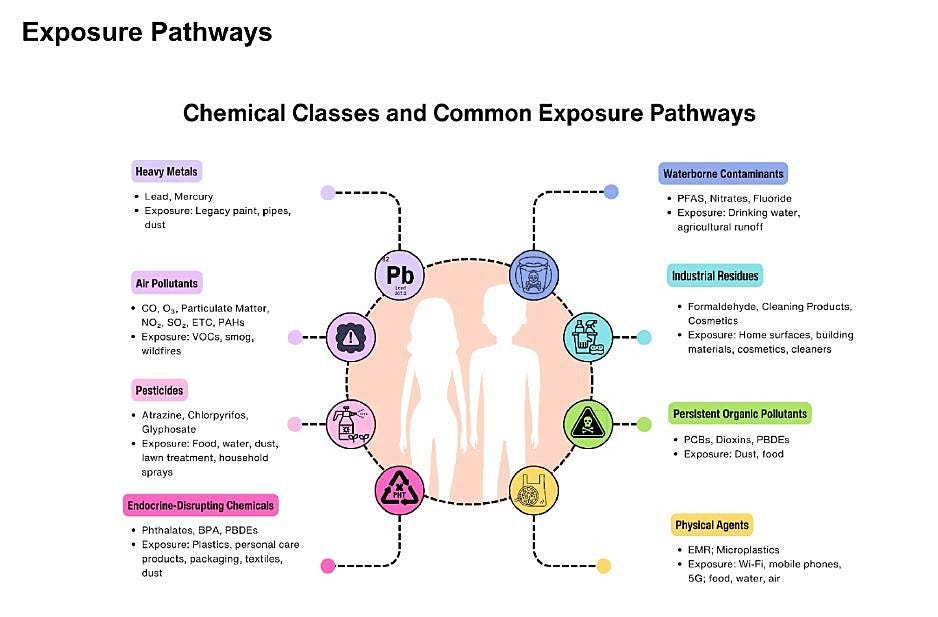

And you’ll find “glyphosate” listed as a “pesticide” in this image:

Here are the references to “pesticides”:

Pesticides, microplastics, and dioxins are commonly found in the blood and urine of American children and pregnant women—some at alarming levels.

Virtually every breastmilk sample (important for infant health, growth, and development) tested in America contains some level of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including pesticides, microplastics, and dioxins. Breastfeeding is the top recommendation for infant nutrition but the data indicates the pervasiveness of the exposures in American life.

The 2009 American Healthy Homes Survey, a collaborative effort by EPA and HUD, demonstrated the widespread presence of pesticides in U.S. homes, with almost 90% showing measurable levels of at least one insecticide on their floors.

More than eight billion pounds of pesticides are used each year in food systems around the world, with the U.S accounting for roughly 11%, or more than one billion pounds.

Children are exposed to numerous chemicals, such as heavy metals, PFAS, pesticides, and, phthalates, via their diet, textiles, indoor air pollutants, and consumer products. Children’s unique behaviors and developmental physiology make them particularly vulnerable to potential adverse health effects from these cumulative exposures, many of which have no historical precedent in our environment or biology.

And here’s what RFK Jr.—who famously bemoaned the “corporate capture” of the food system and fired scores of civil servants ostensibly because of their unwillingness to challenge the status quo—said Tuesday at a hearing of the Senate Appropriations Committee:

There's a million farmers who rely on glyphosate. 100% of corn in this country relies on glyphosate. We are not going to do anything to jeopardize that business model.

TITLE: Pesticide manufacturers ask lawmakers for immunity from lawsuits by sick farmers

https://investigatemidwest.org/2025/05/21/pesticide-manufacturers-ask-lawmakers-for-immunity-from-lawsuits-by-sick-farmers/

EXCERPTS: Ray Bickel spent over a decade driving a truck through giant corn and soybean fields in Clinton County, Iowa, applying pesticides. He says it was good work, while it lasted.

In 2017, he had a heart attack. The doctors ran tests to find out what caused it and found something else. “He was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which is blood and bone marrow cancer. And he was diagnosed with stage three rectal cancer,” his wife, Margarette Bickel, said.

Doctors suggested it could be because of his years working with Roundup, a widely-used herbicide. Now he is one of many farmers suing the maker, Monsanto, which is owned by Bayer.

[I]n recent years, Bayer, which now manufactures Roundup, has faced approximately 181,000 lawsuits claiming that this pesticide, particularly its main ingredient, glyphosate, causes personal injuries, including cancer.

Most of the civil lawsuits against Bayer argue that the company failed to warn Roundup users of potential cancer risks. Applicators like Bickel can spend more than 12 hours a day spraying Roundup for many days straight during the growing season.

“It didn’t have a warning on there about this could cause cancer or anything like that,” said Bickel. “So, I don’t know — I might not have gotten too many instructions about safety.”

Without clear warnings, he assumed he didn’t need to take precautions as the chemical settled on his skin during application.

“It didn’t have an odor, so you assumed that it wouldn’t hurt you,” Bickel said. “I don’t know — water doesn’t have an odor and it doesn’t hurt you, so I guess we assumed Roundup was the same way.”

“Failure to warn” suits rely on state liability laws. The pesticide immunity bills being introduced around the country would offer protection from that argument as long as the labeling on pesticides is otherwise compliant with federal regulations.

Immunity bills have been proposed in Florida, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Wyoming. Similar bills have already been signed into law in North Dakota and Georgia.

The legislation would make it harder for people to sue pesticide companies, even if they believe a product caused serious health problems.

Opponents of the immunity bill want explicit warning labels to protect users like Bickel: a warning that the product may cause cancer, not to get it on your skin, and to wear adequate protection when spraying it.

“Educating farmers on the safe use of herbicides — what protective gear you have to wear, under what circumstances, and that type of thing — that’s really where we ought to be spending our energy, rather than saying this group of folks can’t use evidence in a court when they’re sick or they’ve gotten ill,” said Aaron Lehman, president of the Iowa Farmers Union, which is against the bill.

Lehman says granting pesticide manufacturers immunity would be unjust.

“It’s unfair that a pesticide company would get to hide behind that label when we don’t get that opportunity as farmers,” said Lehman. “If we do something wrong, we’re liable on our farms, right? [The bill] definitely favors and tilts the playing field away from farmers toward the pesticide makers.”

Bayer officials deny that Roundup causes cancer.

They pointed to a 2018 peer-reviewed paper called the Agricultural Health Study, published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. That study followed pesticide applicators’ health through surveys and found no link between solid tumors or lymphoid malignancies and glyphosate.

Lynelle Phillips, an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Public Health at the University of Missouri, evaluated the Agricultural Health Study cited by Bayer.

“There were a lot of flaws in that study,” Phillips said, noting her opinions are her own and don’t represent the university.

For example, initial survey results only spanned about six years “and usually for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, you need at least 10—more like 20 to 30—years to go by,” Phillips said. A second survey was done a decade later, but the response rate was low, Phillips said, which doesn’t make for reliable data.

Some of the other studies Bayer uses to back its safety claims might be unreliable, as well, Cook said.

“If you look at the studies Bayer submitted to the EPA when the label was being developed and the product was approved for the market, they were, for the most part, studies that were requested and endorsed by Bayer and Monsanto,” Cook said.

Because there is disagreement about glyphosate’s safety even in the scientific literature, Phillips said looking at papers that review various studies can be helpful. For example, a 2021 meta-analysis of different studies by Dennis D. Weisenburger found that “the epidemiologic studies provide ample evidence for an association between exposure to [glyphosate] and an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.”

“It does seem to be carcinogenic,” said Phillips.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer, an agency within the World Health Organization responsible for cancer research, also analyzed available peer-reviewed studies from the scientific literature. They found that glyphosate is probably carcinogenic to humans.

TITLE: Safe for Michigan farms or poison? Battle intensifies over future of Roundup

https://www.bridgemi.com/michigan-environment-watch/safe-michigan-farms-or-poison-battle-intensifies-over-future-roundup

EXCERPTS: With the election of President Donald Trump, the conflict over glyphosate’s risks and benefits entered a new realm of confrontation that has the potential to alter its stature as the favored chemical tool in agriculture, the largest user of fresh water in the blue economy of Michigan and the Great Lakes.

Lee Zeldin, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, is supporting a new regulation that would stabilize glyphosate’s continued use by immunizing it from any claims of injury. The rule is consistent with legislation under review in Congress and introduced in 10 states.

But Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, also is the country’s most prominent glyphosate opponent, calling it a “poison.” Kennedy has focused on limiting exposure to glyphosate as a feature of his Make America Healthy Again campaign to combat chronic disease. “There are many, many diseases linked to glyphosate exposure,” Kennedy told Joe Rogan, an influential podcaster, in 2023.

The urgency of glyphosate’s suspected hazards increased dramatically in 2015 when the International Agency for Research on Cancer, a respected unit of the World Health Organization, classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

The finding pushed glyphosate to the center of ferocious disagreement in Europe and the United States about its safety.

Austria, Belgium France, and the Netherlands enacted bans on household use of glyphosate. Germany and Portugal banned it in public spaces.

Following the 2015 IARC carcinogenic classification Americans began to file lawsuits to recover financial damages for cancers they asserted were caused by glyphosate. Bayer set aside $16 billion to settle claims and since 2018 has paid over $14 billion in judgments to 115,000 Americans who asserted they weren’t warned about the chemical’s hazards. In the newest verdict, a Georgia jury awarded nearly $2.1 billion in damages in March to a plaintiff who claimed Roundup caused his cancer and he wasn’t sufficiently warned.

Kennedy’s appointment to Trump’s cabinet as the health secretary raised more alarms at Bayer, which fears the U.S. might follow the trend in Europe and severely regulate glyphosate. Kennedy served on the legal team that won the first jury verdict in 2018 that awarded $290 million to a California groundskeeper who asserted that exposure to Roundup was the source of his non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Kennedy has focused on limiting exposure to glyphosate as a feature of his Make America Healthy Again campaign to combat chronic disease. The day after Kennedy was sworn in, President Trump activated Kennedy’s initiative with an executive order to “aggressively combat the critical health challenges facing our citizens.” In his first address to the agency’s staff in February Kennedy said "nothing is going to be off limits" in the department's work, including pesticides like glyphosate.

Health authorities, families of people injured by the chemical, and legislators who’ve studied the risks say it’s well past the moment when the chemical’s hazards should prompt more intensive restrictions on its use. Here’s why. In testimony in class action lawsuits brought against Bayer, researchers have described how the formula for Roundup includes a sister chemical that enables glyphosate to penetrate through leaves, be transported by the vascular system to the roots, and kill the plant.

The same chemical penetrates human skin enabling glyphosate to reach the bloodstream and bone marrow, where white blood cells form. Research on the behavior of glyphosate in the marrow has found it is capable of causing genetic mutations in developing white blood cells. With regular exposure to glyphosate, from spraying it on farm fields or applying it to kill weeds on lawns and gardens, enough mutations can occur to lead to lymphoma, a cancer that results from white blood cells growing out of control.

“This is one of the big reasons that dermal exposure is a much more dangerous route of exposure than dietary exposure,” said Benbrook. He added that EPA needs to add more stringent safety guidelines to glyphosate’s label that specifically warn of its cancer-causing potential.