DAILY TRIFECTA: Insurers Take Advantage Of Medicare

Running short on life preservers

THE SET-UP: The is GOP is currently using waste, fraud & abuse™ as a misdirecting euphemism for cutting Medicaid eligibility and benefits.

Meanwhile … Medicare, as you’ll see in today’s EXCERPTS, is entangled in actual waste, fraud & abuse via the Medicare Advantage privatization scheme.

Medicare Advantage initially “grew out of the idea that the private sector could provide healthcare more economically.” As the Wall Street Journal notes, it’s ballooned into a “$450-billion-a-year system” that covers “more than half of the 67 million seniors and disabled people on Medicare.” That kudzu-like growth would be a boon for taxpayers and beneficiaries if the magical power of the “private sector" to do it “more economically” was a real thing.

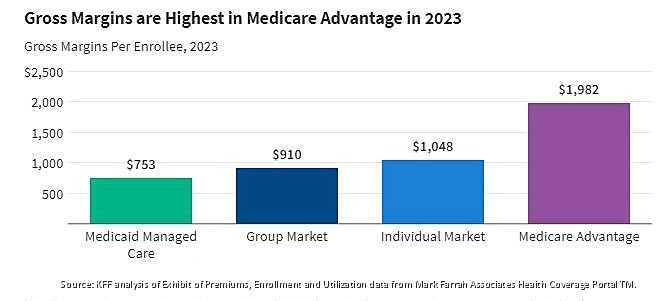

As it stands, Medicare Advantage costs an additional 22% per enrollee. That translates into an annual “overpayment” of $83 billion. It’s a “cash monster” that’s also been repeatedly defrauded by insurers. Cigna was forced out of the Medicare Advantage business last year after paying $172 million to settle accusations it used false diagnostic codes “to boost reimbursement.” They are not alone. A Wall Street Journal investigation published in July found UnitedHealth Group and Humana at the scenes of similar crimes. Both were reimbursed by taxpayers for treating medical conditions that either didn’t exist or were systematically exaggerated by staff. At the same time they minimized overhead by issuing denials for care they’d otherwise have to give. If insurance is a racket … they’re playing doubles.

The Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General reviewed the charges laid out in the Wall Street Journal’s story. They found some smoke. But UnitedHealth Group is reportedly working to convince them there’s no fire … and understandably so. The “Medicare and Retirement” business is United Healthcare’s largest source of revenue, bringing in a healthy $129 billion in 2023. Last year it projected an “8% to 10% long-term revenue growth rate,” along with some additional gains in its Medicaid business … because that’s being privatized, too. Although Medicaid’s margins are not nearly as “gross” as those coughed-up by the “cash monster.”

The upshot is that Medicare Advantage recipients get the worst of both worlds—taxpayers pay (and over-pay) for “socialized medicine,” but they get privatized, profit-seeking health insurance in return. That public-private integration has turned healthcare into an “industrial complex” like the defense industry …. with insurers guaranteed a perpetual piece of all our healthcare action.

And there’s a lot of action.

The combination of both public and private spending is, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), “projected to climb from $4.8 trillion, or $14,423 per person, in 2023 to $7.7 trillion, or $21,927 per person, in 2032.” Overall, it will expand from “17.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) … to nearly 20 percent by 2032” over the same period. It’s why the consultants at McKinsey & Company predict “healthcare profit pools will grow at a 7 percent CAGR [Compound Annual Growth Rate], from $583 billion in 2022 to $819 billion in 2027.” They also identified several particularly inviting “profit pools” for buoyant investors:

Medicare Advantage, spurred by the rapid increase in the “duals population” (“duals” are eligible for both Medicare & Medicaid)

outpatient care settings such as physician offices and ambulatory surgery centers

the software and platforms businesses (see algorithms and A.I.)

“specialty” pharmacy services (per WebMD: these pharmacies offer “medications used to treat rare or complex health problems” )

“Profit pools.” It’s evocative jargon for an industry that’s drowning Americans in $220 billion of medical debt. Weighed down by rising premiums and growing gaps in coverage, more and more Americans find themselves barely treading water (or worse) in the deep end of the profit pool. Meanwhile, their access to actual healthcare seems to be drying up … while the people who issue denials are swimming in cash. They can thank the sharks who feed on seniors seeking help finding a Medicare Advantage plan. They ask for help because it’s complicated … just take a look at this breakdown of the Medicare System. It’s almost as if someone is intentionally chumming the waters. - jp

TITLE: Trump’s DOJ Accuses Medicare Advantage Insurers of Paying ‘Kickbacks’ for Primo Customers

https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/justice-department-accuses-medicare-advantage-insurers-kickbacks-top-customers/

EXCERPTS: When people call large insurance brokerages seeking free assistance in choosing Medicare Advantage plans, they’re often offered assurances such as this one from eHealth: “Your benefit advisors will find plans that match your needs — no matter the carrier.”

About a third of enrollees do seek help in making complex decisions about whether to enroll in original Medicare or select among private-sector alternatives, called Medicare Advantage.

Now a blockbuster lawsuit filed May 1 by the federal Department of Justice alleges that insurers Aetna, Elevance Health (formerly Anthem), and Humana paid “hundreds of millions of dollars in kickbacks” to large insurance brokerages — eHealth, GoHealth, and SelectQuote. The payments, made from 2016 to at least 2021, were incentives to steer patients into the insurer’s Medicare Advantage plans, the lawsuit alleges, while also discouraging enrollment of potentially more costly disabled beneficiaries.

Policy experts say the lawsuit will add fuel to long-running concerns about whether Medicare enrollees are being encouraged to select the coverage that is best for them — or the one that makes the most money for the broker.

Medicare Advantage plans, which may include benefits not covered by the original government program, such as vision care or fitness club memberships, already cover more than half of those enrolled in the federal health insurance program for seniors and people with disabilities. The private plans have strong support among Republican lawmakers, but some research shows they cost taxpayers more than traditional Medicare per enrollee.

The plans have also drawn attention for requiring patients to get prior authorization, a process that involves gaining approval for higher-cost care, such as elective surgeries, nursing home stays, or chemotherapy, something rarely required in original Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans are under the microscope for aggressive marketing and sales efforts, as outlined in a recent report from Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.). During the last year of the Biden administration, regulators put in place a rule that reined in some broker payments, although parts of that rule are on hold pending a separate court case filed in Texas by regulation opponents.

The May DOJ case filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts alleges insurers labeled payments as “marketing” or “sponsorship” fees to get around rules that set caps on broker commissions. These payments from insurers, according to the lawsuit, added incentives — often more than $200 per enrollee — for brokers to direct Medicare beneficiaries toward their coverage “regardless of the quality or suitability of the insurers’ plans.” The case joins the DOJ in a previously filed whistleblower lawsuit brought by a then-employee of eHealth.

“In order to influence the market, the Defendant Insurers understood that they needed to make greater, illicit payments in addition to the permitted (but capped)

In one example cited, the lawsuit says insurer Anthem paid broker GoHealth “more than $230 million in kickbacks” from 2017 to at least 2021 in exchange for the brokerage to hit specified sales targets in payments often referred to as “marketing development funds.”

Insurers and brokers named in the case pushed back. Aetna, Humana, Elevance, eHealth, and SelectQuote each sent emailed statements to KFF Health News disputing the allegations and saying they would fight them in court. EHealth spokesperson Will Shanley, for example, wrote that the brokerage “strongly believes the claims are meritless and remains committed to vigorously defending itself.” GoHealth posted online a response denying the allegations.

The DOJ lawsuit is likely to add to the debate over the role of the private sector in Medicare with vivid details often drawn from internal emails among key insurance and brokerage employees. The case alleges that brokers knew that Aetna, for example, saw the payments as a “shortcut” to increase sales, “instead of attracting beneficiaries through policy improvements or other legitimate avenues,” the lawsuit said.

One eHealth executive in a 2021 instant message exchange with a colleague that is cited in the lawsuit allegedly said incentives were needed because the plans themselves fell short: “More money will drive more sales [be]cause your product is dog sh[*]t.”

TITLE: Brokers accused of steering seniors into a Medicare Advantage ‘trap’

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/brokers-accused-of-steering-seniors-into-a-medicare-advantage-trap-79ab97ce

EXCERPTS: In the latest issue of JAMA, Cornell’s Lawrence Casalino, Amelia Bond and Dhruv Khullar calculate that an insurance broker can land nearly $6,000 in lifetime commissions by selling a 65-year-old a privatized Medicare Advantage plan. Meanwhile they will likely earn only “50% to 70%” as much if the client instead opts for government-run original Medicare, supplemented by private Medigap and Part D prescription plans.

Federal regulations cap sales commissions on Medicare Advantage plans at $626 in the first year, they write. But the broker is allowed to get up to half that amount, or $313, for every year the enrollee stays on the policy. As people aged 65 have an average life expectancy of 18 years, “this generates $5,947 in commissions” for a Medicare Advantage policy, the Weill Cornell Medical College researchers point out.

Meanwhile, commissions that a broker is likely to get for selling Medigap and Part D private health plans to an enrollee in traditional, government-run Medicare “are likely to sum to 50% to 70% of this total,” they estimate.

That would be $3,000 to $4,200.

Worse, they argue, seniors missold Medicare Advantage plans then find themselves in a “trap” — their word. “It is very difficult for most beneficiaries, once enrolled in MA, to switch to traditional Medicare,” they write. That’s because, with a few exceptions, those who want to switch from Medicare Advantage to original Medicare may find it difficult, very expensive or even impossible to secure a supplemental “Medigap” policy to cover the 20% of costs that original Medicare doesn’t pay.

You are generally — again, with a few exceptions — only guaranteed a good deal on Medigap when you are first able to sign up, at age 65. Medicare Advantage, like Hotel California (or a lobster trap) is easier to get into than to leave.

Many beneficiaries “do not understand … that by enrolling in MA, they are making what is likely to be an irreversible, lifelong decision,” the researchers write.

They have fresh data to show the effect of this. Four states — Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York — make it easy to leave Medicare Advantage by guaranteeing a good deal on Medigap if an enrollee does. And in those states, as a result, between 2014 and 2022 the numbers of “high need” patients switching back to original Medicare is nearly 400% higher than in the other 46 states, they found.

The National Association of Benefits and Insurance Professionals, the trade association of the insurance brokers, disagreed. “Due to lower renewal commissions, the gap between Medicare Advantage (MA) and Medicare Supplement (Med Supp) compensation narrows after a few years,” the organization said in a statement. “The difference in MA plan compensation is often just a few dollars.”

Instead NABIP blamed insurance companies for the misselling of Medicare Advantage plans, accusing them of “aggressive and misleading marketing targeting seniors.”

TITLE: UnitedHealth Built a Giant. Now Its Model Is Faltering.

https://www.wsj.com/health/healthcare/unitedhealth-business-model-struggles-c7238dc4

EXCERPTS: American healthcare is a patchwork of markets: government-run programs such as Medicare and Medicaid alongside a commercial sector dominated by employer-sponsored insurance. UnitedHealth became a major player in most markets. It was in the privatized version of Medicare, known as Medicare Advantage, where UnitedHealth’s scale made an outsize impact on profits, helping it grow faster and capture more revenue from taxpayers.

The idea behind the program is that by managing care more actively, private insurers could reduce costs for the government. Yet over time, news reports, lawsuits, and whistleblower claims have alleged that insurers exploited the program’s design to overbill. A Wall Street Journal investigation last year found that UnitedHealth collected billions in additional payments tied to questionable diagnoses.

As long as Medicare Advantage remained highly profitable, UnitedHealth’s size was a clear advantage. Its leadership in the program, both as an insurer and as a provider through Optum, prompted rivals such as CVS Health to seek to imitate its vertical integration strategy.

The landscape began to shift, however. Amid mounting scrutiny, the Biden administration introduced policy changes that reduced what insurers could bill. The changes landed just as medical costs were accelerating—a one-two punch that squeezed both revenue and margins.

The entire sector felt the pressure: Humana and CVS saw their stocks crater last year as costs escalated, crimping their margins. At first, UnitedHealth appeared relatively protected. When competitors pulled back, it doubled down—absorbing more patients across both its insurance and provider businesses in 2024.

But elevated medical utilization caught up with it, too. And because UnitedHealth doesn’t just insure patients—it also runs clinics that treat them through Optum—when costs rise more than expected, it gets hit as an insurer having to pay out more in claims, and again as a provider, absorbing the higher cost of delivering that care. The pain is made worse when regulation cuts the payments that flow through this system.

In the past, UnitedHealth might have offset margin pressure by making sure that its patients are coded for as many conditions as its army of doctors see fit. With new constraints in place, that lever became harder to pull. “The inability to code…well above the rest of the industry represents a potentially fundamental impairment of UNH’s historical competitive advantage,” wrote Ryan Langston, an analyst at TD Cowen.

At the same time, UnitedHealth’s use of certain tools to control costs might have eased up. The insurance arm uses things such as artificial intelligence analytics and prior authorization as ways to control utilization. But those same tools also drew scrutiny that intensified amid a political backlash.

Then came the December assassination of Brian Thompson, who led the insurance unit. The incident was widely condemned by political leaders. But it also triggered public support for the suspect in the shooting and death threats against industry executives, leading to heightened security measures across the industry.

Amid the rising political pressure, UnitedHealth began relaxing some of its prior-authorization protocols. On a January earnings call, Witty pledged to “speed up turnaround times for approval of procedures and services for Medicare Advantage patients.” For instance, starting in January, UnitedHealthcare waived prior authorization for Medicare members before certain outpatient therapy visits. The company pointed to such changes as part of an effort to modernize the system and said that they weren’t to blame for higher medical costs in the first quarter.

Still, some analysts have wondered if the loosening of prior authorization controls are emerging as cost drivers. “UNH may be relaxing prior authorization and other claims controls in response to policy pressures,” wrote Lance Wilkes, an analyst at Bernstein.

Even after the recent turbulence, UnitedHealth remains the industry goliath, with nearly 400,000 employees that serve millions of Americans nationwide. With mounting financial and political pressure, however, the company’s tremendous size might have become more of a burden than a strategic advantage.

SEE ALSO:

UnitedHealth downgraded by investment banks

https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/unitedhealth-downgraded-td-cowen-bofa-raymond-james/748516/

UnitedHealth Stock Rallies From 5-Year Lows as CEO and Other Insiders Scoop Up Shares

https://www.investopedia.com/unitedhealth-stock-rallies-from-5-year-lows-as-ceo-and-other-insiders-scoop-up-shares-11737917