DAILY TRIFECTA: Good Luck Changing The Climate Of Denial

But Isn't The Pope Infallible?

TITLE: The pope leads 1.4 billion Catholics. Getting them to care about the climate is harder than he thought.

https://grist.org/international/the-pope-leads-1-4-billion-catholics-getting-them-to-care-about-the-climate-is-harder-than-he-thought/

EXCERPT: The pontiff’s deep personal connection to the issue is perhaps best exemplified by his being the first pope to take the name of Francis of Assisi, a saint known for his solidarity with the poor and his love of the natural world. Francis, who also is the first pope from Latin America, has channeled his namesake by seeming to intuitively understand that caring for marginalized people is impossible without caring for the land, water, and air they rely on. Throughout his papacy, he has repeatedly emphasized the connection between “the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor,” as he wrote in Laudato Si’.

For Catholics already working on climate, Francis’ latest exhortation may provide a reenergizing reminder that the Vatican is behind them, and that they are doing the right thing. “As a Catholic environmental family, we were completely thrilled at this,” said Christina Leaño, assistant director of the Laudato Si’ Movement. “It just gives us that extra motivation and excitement and hope.”

The very existence of Leaño’s organization is a testament to the impact the pope’s focus on climate has already had. Since the release of Laudato Si’, organizations focused on mobilizing Catholics to action have blossomed all over the globe, especially in Asia, South America, and Africa, where clergy and laity alike have been grappling with the crisis for years. Filipino bishops have, for example, called for Catholic institutions’ divestment from coal and transitioned their own parishes to solar. The archbishop of the Democratic Republic of Congo facilitated 12 days of “African climate dialogues” to highlight how the continent is impacted by climate change.

But Leaño recognizes that “there’s still quite a gap” between the Holy Father’s official statements and what is preached during weekly Mass here in the U.S. “If you talk to the average churchgoer, they will say that they have never or rarely heard about climate or environmental issues from the pulpit,” she said.

Sharon Lavigne is a devout Catholic whose work stopping a $1.25 billion plastics manufacturing plant from being built in her community earned her a 2021 Goldman Prize. Yet she hadn’t heard anything about Laudate Deum before Grist asked her about it. “I know in my church, we haven’t done anything [about the climate and pollution],” she said. “We haven’t even mentioned it.”

So why hasn’t one of the clearest priorities of the highest authority in the Catholic church been widely embraced here? One clue comes from the ways American Catholicism mirrors American politics.

One in four people in the United States identify as Catholic. A small but vocal number of them — a group that includes some bishops — has spent the last few years building a campaign that claims Francis is not the real pope, just as some within the Republican Party claim Joe Biden is not the real president. The point is to undermine Francis’ authority, said Fortenberry.

“The only way to square the circle that the guy at the top is making these extremely clear statements about church doctrine that are incompatible with certain aspects of right-wing ideology is to say that he’s not the pope,” she said.

If the pontiff seems frustrated, it’s no doubt because global emissions keep rising — but it’s likely also due to his encountering so many “dismissive and scarcely reasonable opinions,” as he wrote in Laudate Deum, from climate deniers within the church.

Though such views are exceptions, recent research shows that the nation’s Catholics are as a whole “no more likely than Americans overall to view climate change as a serious problem.” As with most people, it’s not denial that impedes action, but the demands of daily life. In Fortenberry’s experience, it’s not that people don’t believe in or care about climate change, it’s that they’re focused on other things.

TITLE: Students Fight for the Right to Learn about Climate Change

https://nonprofitquarterly.org/students-fight-for-the-right-to-learn-about-climate-change/

EXCERPT: “Our generation is on the front lines of this fight and it’s time for our school districts to take real action,” Sunrise Movement organizer Crandall told the Hill.

The group formed in direct response to the denial of climate change and the mounting legislation in Republican-led states discouraging or outright banning the teaching of climate science in schools. The proposed legislation would provide funding to update schools, and to hire additional teachers and modernize curricula.

“We don’t learn about climate change at all,” 16-year-old Summer Mathis, a student in Georgia, told the Guardian, which reported that under that state’s “dismissive concepts” law, “teachers are unable to talk about climate justice and the unequal toll of global heating. In other Republican-led states, factual climate education is being targeted directly.” Texas, Idaho, and Florida are but a handful of the states stripping mention of climate change from textbooks or supporting teaching materials from conservative groups, which often include climate change denial and other dangerous misinformation.

“Being a youth right now is really scary,” 15-year-old Aster Chau told the Guardian. “It’s really scary knowing that I’m underage, and can’t vote to elect the people making these big decisions about our futures, not having a say in that.” Though Chau acknowledged “feeling the weight of the climate crisis,” the student from Pennsylvania also spoke to the power of having peers. “Being with one another is really helpful, knowing that I’m not just the only one who is feeling this pressure, but also extreme passion in fighting it.”

TITLE: The Climate Denial Machine’s Fake Statistics Just Keep On Coming

https://c4ss.org/content/59083

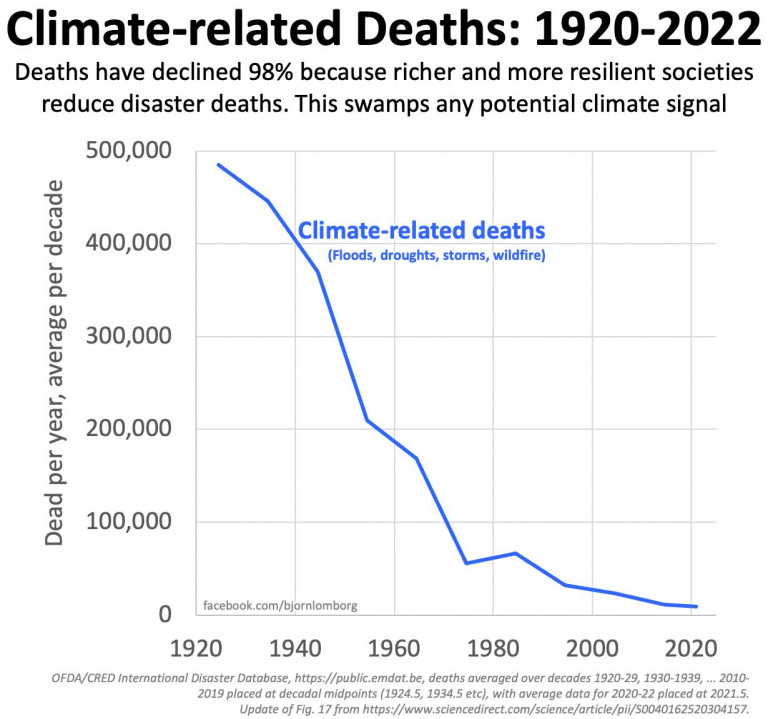

EXCERPT: The thing that prompted this column was a misleading infographic [Bjorn] Lomborg posted on Facebook, summarizing data from his article “Welfare in the 21st century: Increasing development, reducing inequality, the impact of climate change, and the cost of climate policies” (Technological Forecasting and Social Change, July 2020). The gist of it, as he summarizes in his Facebook post, is that “about 98% fewer people died in 2022 than a hundred years ago from climate-related natural disasters like floods, droughts, storms, and wildfires…. Over the past hundred years, annual climate-related deaths have declined by more than 98%.”

Lomborg’s graph probably appears more frequently in online right-libertarian polemics than anything since the equally stupid “World Population Living in Extreme Poverty, 1820-2015” graphic that’s been circulating for years. The leading places it shows up are “Human Progress” (a Cato subsidiary), the Wall Street Journal, and the Foundation for Economic Education. Vivek Ramaswamy, the living personification of obnoxious techbrohood, quoted it in a recent 2024 GOP presidential candidates’ debate — the gold standard for Stoopid.

Let’s start with the data itself. What does Lomborg even count as “climate-related” deaths? Apparently not people who die in actual heat waves. There were 60,000 heat-related deaths in Europe alone during Summer 2022 — the highest death toll since the 70,000 in Summer 2023 — and Lomborg’s total for all climate-related deaths, for the whole world, doesn’t even appear to hit the 10,000 mark on his graph. In South Asia, low heat-related death counts under far more extreme conditions raised suspicion of undercounting; an estimate based on excess mortality, which requires months of data analysis to produce, would likely have resulted in a figure of many thousands. This reasoning is borne out by the fact that the 2015 heat wave resulted in 2000 deaths in Pakistan’s Sindh province alone. In the United States, in Maricopa County Arizona alone, reported heat-related deaths this year had reached 180 as of September 6. This was likely an undercount, considering last year’s total was revised upward to 450 at the end of the summer. Heat-related deaths, again, are prone to undercount. “If there are comorbidities — heart disease, obesity, mental illness — heat might not make it on the list.”

And in poorer areas — the very places likely to have higher death rates because of vulnerable populations without air conditioning and other means of dealing with extreme heat — the undercount is likely to be exacerbated because of inadequate government resources. As Zoya Tierstein notes,

properly diagnosing a death as climate-related requires time, training, and resources that many of the nation’s roughly 3,500 health departments don’t have. While Maricopa County carefully combs through every suspected heat-related death that occurs in the county during Arizona’s long summer, it’s an outlier in that respect.

This is equally true of deaths from heat-related disasters like hurricanes.

It’s hard to get a full picture of the true number of mortalities connected to a given disaster in real-time. The full death toll often isn’t revealed until weeks, months, even years after the event occurs. And an unknown fraction of deaths often slide by undetected, never making it onto local and federal mortality spreadsheets at all. For example, a recent retrospective study found the number of people who died from exposure to hurricanes and tropical cyclones in the U.S. in the years between 1988 to 2019 was 13 times higher than the federal government’s official estimates.

But even stipulating to the validity of Lomborg’s statistical claims, the inferences he draws from them don’t — to put it mildly — display a whole lot of intellectual rigor. His argument basically boils down to this: “Despite one degree Celsius increase in temperature since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, climate-related deaths have fallen by 98% over the past century. So there is no basis for predicting a billion excess deaths from another degree or more increase over the coming century.”

In other words, he’s extrapolating a past century’s trends another century into the future, on the tacit assumption that nonlinear phenomena, tipping points, and positive feedback loops don’t exist. Given the nature of the phenomena in question, and actual climate news over the past decade or so, that’s an extremely unjustifiable assumption to make.

Consider: The New York Times reported in January that the previous eight years were the eight hottest on record. Since then, 2023 has broken the record for hottest ever. At 1.5 Celsius degrees cumulative temperature increase, five different climate tipping points become likely; two of them in particular — the collapse of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, and alteration of the Gulf Stream ocean current — will have absolutely catastrophic non-linear effects in a very short time period. Hundreds of millions or billions of people live in areas that will be flooded by ice sheet collapse. Other tipping points, like methane emissions from thawing permafrost, involve positive feedback cycles that by definition are non-linear. What’s more, there are more recent findings that “tipping points and cascades are already occurring, not at 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius of warming, but right now” — suggesting that “many positive feedbacks are not fully accounted for in climate models.”

Meanwhile, the maximum theoretical limit of human heat tolerance is a wet bulb temperature of 95 Fahrenheit — that is, at 100% humidity — for six hours. As these conditions prevail in more and more areas of the world for extended periods, and local temperatures exceed the limits of human survival, we can expect a dramatic difference between death rates before and after.

This kind of sophistry isn’t limited to Lomborg’s treatment of climate-related deaths; he’s used the same argument regarding sea level rise: “Lomborg compares the observed past rise with average projections for the future.”

So even if the data is valid — which it is not — without the critical capability to interpret it, it’s worthless.