DAILY TRIFECTA: Cry Me An Atmospheric River

She dropped a bomb on us

THE SET-UP: A bomb cyclone just “dropped” on the Northwest and it is ushering-in an atmospheric river to the south that promises to drench Northern California. Flooding and mudslides in recently-burned areas are predicted. Amazingly, this is the third consecutive winter an atmospheric river has washed over the state. In fact, multiple rivers have battered the state after a prolonged period of drought. These wild swings epitomize the reality of an anthropogenically-altered climate … a reality denied by the incoming administration. Denial is not just a river in Egypt, it is an atmospheric river that brings once-in-generation storms multiple times per year.

Ironically, repeated once-in-a-generation storms stoked by our climate pollution unleashes naturally sequestered methane—a climate polluting gas. The more we push, the more Mother Nature pushes back. It’s an elemental Newtonian Law we continue to break at our own peril. And good luck getting your home insured. - jp

TITLE: What's a bomb cyclone? 4 facts about the winter storm

https://www.9news.com/article/weather/severe-weather/what-is-a-bomb-cyclone-facts-about-the-winter-storm/536-2f6dcff5-6a3e-4377-af9c-766022d3e0f4

EXCERPTS: A bomb cyclone is a storm that “intensifies very rapidly,” Jennifer Francis, Ph.D., senior scientist with the Woodwell Climate Research Center, told VERIFY.

This type of storm is created by a process known as bombogenesis, which occurs when atmospheric pressure at the center of the storm drops quickly – specifically, one millibar or more per hour over a 24-hour period.

A bomb cyclone can bring dangers such as strong winds, heavy precipitation in the form of rain and snow, and coastal flooding to impacted areas, Greg Carbin, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, told VERIFY.

The combination of snow with these strong winds can lead to blizzard conditions, shutting down airports and roads, Francis added.

Bomb cyclones, as is the case with other storms, form due to contrasting air masses – one that’s very cold combined with another that’s very warm.

The storms also get energy from disturbances in the jet stream, a narrow band of strong wind in the upper level of the atmosphere.

Climate change also impacts the development of bomb cyclones and other severe storms “in a number of very direct ways,” Francis, whose expertise lies in arctic weather and climate, said.

“One is that the oceans are warming very steadily because of our increased emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere,” she said. “That extra warming in the oceans is increasing that contrast between that very cold arctic air coming down and the warm, moist air that’s feeding the air mass to the east of that arctic air.”

Additionally, warming of the air and oceans leads to an increase in evaporation, meaning there is more water vapor in the atmosphere, Francis said.

That water vapor condenses into clouds, releases heat and adds energy to storms, similar to what happens with a hurricane. It also provides more moisture to fuel the storm, Francis said.

“We’re seeing a major uptick in the frequency of heavy precipitation events, and this is certainly connected to this increase in water vapor that’s in the atmosphere as a result of the warming oceans and air,” she added.

Jonathan Overpeck, Ph.D., a climate scientist and professor at the University of Michigan, also says major winter storms like bomb cyclones are becoming “more likely and more destructive” due to climate change.

TITLE: Compound weather events found to have greater effect on wetland methane emissions than discrete weather extremes do

https://phys.org/news/2024-11-compound-weather-events-greater-effect.html

EXCERPT: Human-caused climate change is driving an increase in extreme weather. Heat waves, droughts, and extreme precipitation are occurring more frequently, growing more intense, and directly affecting ecosystem function. For instance, the 2003 European heat wave—the continent's hottest summer in centuries—caused a substantial die-off of Sphagnum moss in alpine bogs, and the bogs took at least four years to recover.

As ecosystems falter under extreme conditions, the exchange of gases between land, water, and atmosphere changes too. For example, under extreme heat, plants prevent water loss by closing off the stoma they use to absorb carbon, leaving more carbon in the atmosphere and creating a feedback loop that can enhance warming.

Wetlands, in which organic material is broken down by microbes underwater to produce methane, are the largest natural source of global atmospheric methane. Using these soggy environs as a natural laboratory, T. J. R. Lippmann and colleagues evaluated how extreme climate events have affected wetland methane emissions at 45 flux tower sites around the world. Their findings are published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles.

The authors used climate data stretching from January 1982 to December 2020 to identify extreme events such as heat waves and droughts. They found both discrete (e.g., only hot) and compound (e.g., both hot and dry) events.

The findings showed that methane emissions were more affected by compound extreme events than by discrete events. Hot-and-dry events led to the largest increases in methane emissions, more so than either hot or dry events. Because droughts can be very long in duration, dry-only extremes led to the largest total decrease in methane emissions.

Heavy precipitation alone did not significantly alter emissions, which the authors say was unexpected because soil saturation is a critical requirement of microbial methane production. Emissions' responses to climate extremes differed by season and by wetland type; marsh and upland sites appeared to be the most sensitive.

Notably, the authors found that the effects of extreme climate events can persist in an ecosystem for at least a year following the end of an event. The findings suggest that as the climate changes, resulting in more hot extremes and fewer cold extremes, wetland methane emissions may increase as well.

TITLE: Cop29: How fast is Earth warming?

https://theconversation.com/cop29-how-fast-is-earth-warming-244093

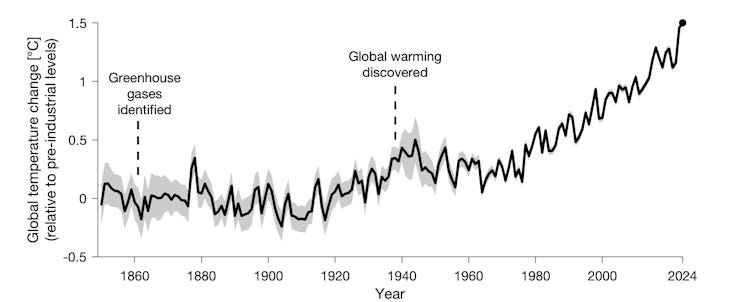

EXCERPT: Negotiators are gathered in Azerbaijan for Cop29 (the latest round of UN climate change negotiations) at a time of great peril. The last two years, 2023 and 2024, were the warmest in records stretching back to the mid-19th century and will be close to 1.5°C above the temperature of the early industrial era. It took a century for the globe to warm the first 0.3°C, but the world has warmed by 1°C in just the last 60 years.

Earth is getting hotter, and at a faster rate.

Earth is probably warming at the fastest pace on record. Ed Hawkins/National Centre for Atmospheric Science

What determines the rate of global warming now is primarily humanity’s emissions of greenhouse gases. If the amount of greenhouse gas we are emitting increases, then the rate at which the world is getting hotter speeds up. Reduce emissions and warming continues, but at a slower pace. Only once emissions are net zero are global temperatures expected to roughly stabilise.

There are other factors and, as a result, the globe has not warmed at the same rate through time. The rate of global warming has been fairly even at 0.2°C per decade from 1970 until now, much faster than any period before. The last two years could suggest the rate is accelerating, though this is not yet clear.

Before 1970 there was a period of slight global cooling due to a rapid increase in reflective aerosol particles being added to the atmosphere, also due to burning fossil fuels. The onset of clean air policies introduced in the 1960s in many western countries reduced this cooling influence. Before the second world war, natural variations in the climate dominated, with a very slow warming influence from early industrialisation.

Nor has the world warmed equally everywhere. Land has typically warmed faster than the global average, with ocean regions warming more slowly. The Arctic is warming fastest of all at up to four times the global average.

What is the outlook for 2025? Persistent warmth during the last two years has slightly surprised climate scientists. But it is more likely than not that 2025 will be cooler than 2024, given the transition to La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. This is the cool phase of a natural cycle known as El Niño Southern Oscillation, or Enso.

And beyond? We will exceed 1.5°C of warming as a long-term average sometime in the next decade or so. Our choices in the next few years will determine whether we can limit global warming to 1.6°C or 1.7°C above pre-industrial levels, or whether the world will continue to warm, with more serious consequences the higher temperatures get.

SEE ALSO:

The 1.5C Climate Goal Is Dead. Why Is COP29 Still Talking About It?

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-11-18/cop29-what-does-1-5c-s-failure-mean-for-climate-negotiations

COP29 A Missed Chance for Climate Pragmatism

https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/COP29-A-Missed-Chance-for-Climate-Pragmatism.html

COP29: Climate finance talks face 'hardest' stage as summit nears end-game

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/climate-finance-talks-face-hardest-stage-cop29-nears-end-game-2024-11-20/